4 Pillars to Achieve Digital Transformation in Aerospace and Defense

Organizations with digital transformation initiatives are making the shift from visionary ambitions to practical projects. To make this transition effective, technical organizations must master how to systematically use data and models, not only during the research and development stages, but also across the project life cycle, including production and maintenance.

The outline of the talk includes:

- What is meant by digital transformation for engineering organizations/projects?

- What are the pillars of digital transformation?

- What are the associated people skills, processes, and technology?

- How to make the transformation effective?

Speaker: Dr. Jon Friedman, Worldwide Aerospace Industry Manager, MathWorks Dr. Jon Friedman is a senior manager at MathWorks in Industry Marketing. Dr. Friedman’s thesis work focused on the application of robust system identification and control theory. After completing the PhD program at University of Michigan, Jon held research and product development positions in the commercial and defense sectors of the automotive and aerospace industries. In addition to experience deploying Model-Based Design, Model-Based System Engineering, and code generation at a Fortune 50 company, he has been a program manager on multiple vehicle programs and led lean engineering and manufacturing projects. At MathWorks, Jon leads a team of industry experts focused on helping leading companies in the aerospace and defense and automotive industries adopt Model-Based Design through sharing of best practices. Dr. Friedman has authored over 50 papers and articles on modeling and Model-Based Design and holds an MBA from the University of Michigan.

Published: 12 Jan 2021

So the topic of my talk today will be the four pillars of digital transformation. But maybe briefly I thought I would just give a quick background on MathWorks. Many people know us as the Matlab company. When I first joined about 15 years ago, I was trying to explain to my father where I was going to work. And he said, oh yeah, the guys that make Matlab.

But more than just making Matlab, we also are the people that work on Simulink and actually about 100 products that are based on top of Matlab and Simulink. And every day we're humbled by the opportunity to work with many of you and work with customers around the world to use this technology.

As I mentioned, there are millions of customers that we work with and engineers and scientists in over 185 countries. And one of the things that I'm again most inspired by is that all of the top 10 automotive and aerospace companies are using our tools every day to accelerate the pace of discovery in engineering and science.

MathWorks itself is a global company we have over 5,000 staff and 33 offices. And we are privately held. And in particular for me, I've had the good fortune to be a part of working with the MathWorks India Team since the day we opened our direct office in 2008. And unfortunately for me this year, this will be the first year since that opening that I won't have an opportunity to travel to India to meet directly with many of you.

MathWorks does have offices in Bangalore, Hyderabad, Delhi, Chennai, and other locations. And as I said, it's a sad day for me because I realize with the passing of this conference, this would have been when I would have traveled to India to be with my colleagues there and to meet with many of you.

But let me get to the topic today, which is what is digital transformation. And when I was asked to speak on this topic, I thought to myself, this is a great question. What is digital transformation?

So I went to the oracle of all things when I have questions-- Google. And I asked Google, what is digital transformation. And Google told me digital transformation is the integration of digital technology into all areas of business, fundamentally changing how you operate and deliver value to your customers. It's a cultural change that requires organizations to continually challenge the status quo, experiment, and get comfortable with failure.

But in truth, sort of Google nature because I had said what is digital transformation, Google highlighted digital. To me, what was really interesting in this definition was changes how we operate and how we deliver value. And fundamentally it's a cultural change.

So these things actually inspired me to think and dive a little bit deeper. What does digital transformation means to the rest of us, those of us that get up every day and perform engineering and science tasks? And we can see this actually within the way that many of our companies and colleagues are meeting this challenge. Caterpillar and Airbus have published their strategies for digital transformation. The European Union and the Department of Defense have also published strategies for addressing digital transformation and digital engineering.

In fact, some of my friends in the Department of Defense have gone so far to explain that digital engineering impacts every aspect of the way that systems are put together, from big data analytics to digital manufacturing, digital twins, topics that many of us have heard about, and the documents long and involved. And for me, it was a lot to take in.

So after doing my own soul searching and consulting the oracle and studying what other companies have thought about, I've come to the idea that there's really four pillars of digital transformation that affect us, one is that model-based system engineering is becoming imperative. The other is that artificial intelligence is now entering the real world. And we need digital tools to be able to meet that need and challenge. That we have to actually change the way that we think about where we do our computing and where we store our data. And lastly, we need new and agile development workflows. And I'll cover a little bit of each of these today to help explain what I mean by them.

So let me start with model-based system engineering. A system engineering itself is a way of dealing with complexity. And it's a methodology and a process to help you avoid omissions and invalid assumptions and manage the fact that the real world is changing.

But again, this is a lot of words. And for me I always think about it from a quote that's attributed to Einstein. He said, if you had an hour to solve a problem, you'd spent 55 minutes thinking about the problem and then five minutes thinking about and working on the solution.

So why is this? Well, this is an aerospace and defense talk, so let's go back to the beginning, which is the Wright brothers. They had a simiple aircraft, lifting services, control surfaces, twin props, and a flat surface to lie on for the pilot.

And as we've moved along, you've gotten to the Spitfire, to the Harrier Jump Jet, to the Tornado. And most recently the UK has decided to go for something they call Team Tempest, which is a system of systems, not a single aircraft. And as you can see at every stage, there's a significant increase in the complexity that has to be managed by the engineering teams that are delivering these systems and systems of systems.

But again, this is a lot to digest. So for me, I think about complexity of the car window. So if we start and we go all the way back to the first cars, there were no windows, so complexity problem solved.

Very quickly, people realized that no windows meant that the elements came into the car, so they added windows and they were fixed, still referred to sometimes as fixed glass in a car. And almost as soon as the glass is fixed, people want the glass to move up and down to let in fresh air when the weather was nice. And so the windows had one, two, or maybe three settings where the glass could be placed.

And then the mechanical engineers came in and they added crank mechanisms and other aspects to allow the window to be more refined in terms of its control. And of course, then the electrical engineers came and added electronics. And then the software engineers came and they added software and additional features so that the window of control itself going up or going down or interact with other systems.

In fact, one thing I noticed when I was renting a car once that the window in the car dropped just as the door was about to close. And I called a friend of mine that worked at that car company and he informed me that the closing effort of the door was too high. And they realized if they vented the window or dropped the window a little bit they could reduce the drag on the door just enough so that as it was closing it met its door closing efforts. And so the window actually is starting to solve usability issues.

And all of this is a lot of complexity, a lot of complexity to communicate across groups, across organizations, across boundaries. And the culture changes-- from the window being a purely mechanical need to one in which it's solving customer problems.

And to do all this you need models, because it's hard to communicate through a series of documents exactly what is needed by the window engineers to make the window do what it's supposed to do and the customer needs. So that's my case for model-based system engineering imperative.

Now, let's talk a little bit about real world artificial intelligence. So to me, there are four parts of developing an artificial intelligence. One is the data preparation. So the speaker before talked about how data is noisy and comes from different systems, different sources.

And this is what really goes into data preparation. It's also the point where humans start to develop some insights. And you can also add additional data through simulation.

The next is to actually develop the AI, the model, and accelerate the training through hardware. There's also a need for stimulation, both to test the AI to fill in where the may need additional training data. And lastly, real world AI gets deployed to embedded systems, to different hardware, to edge devices.

So let's dive into this just a little bit. Data preparation and management turns out to be one of the most critical aspects of successful AI development. And it's actually quite hard.

Today, the data comes from multiple sensors, databases, structured, unstructured, spans time, different time intervals. As I mentioned, it can be noisy and it represents lots of different domains. And the data needs to be prepared for the next step. And this can be quite time consuming.

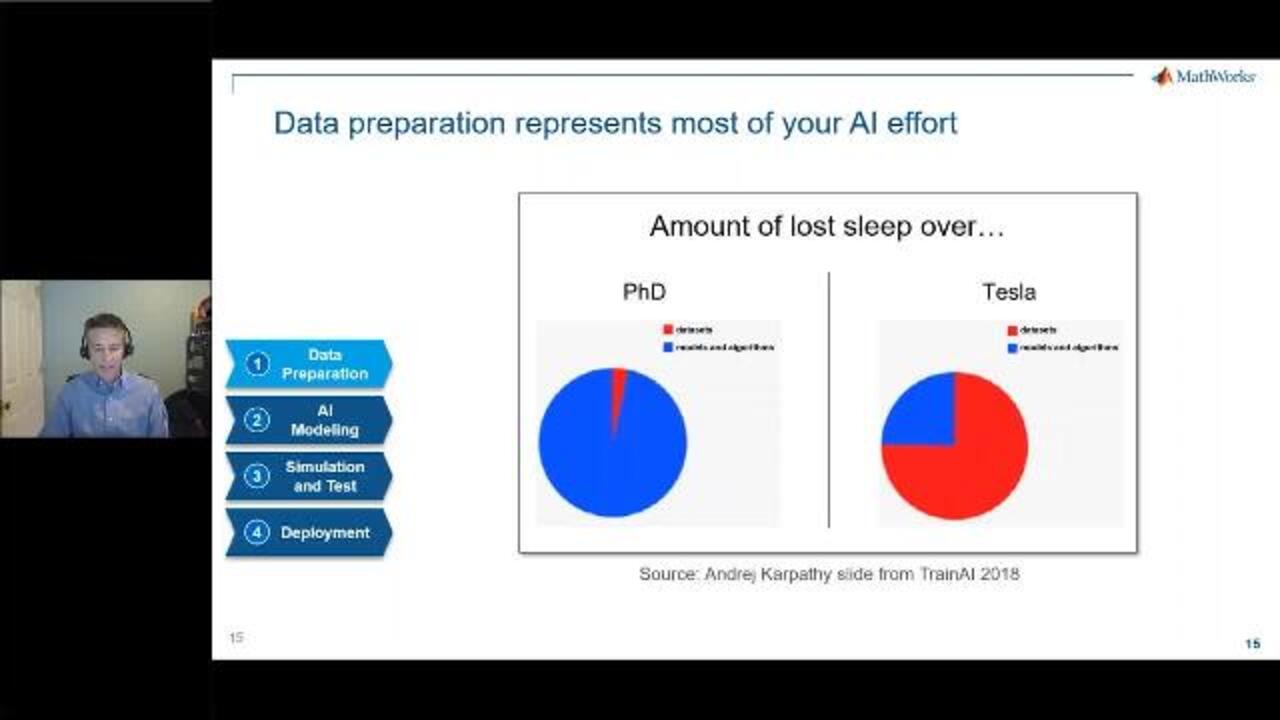

In fact, a good way of thinking about this comes from a case study from Andrej Karparthy, who in his 2018 talk said while doing his PhD work at Stanford he didn't feel that he needed to spend much time on the data because he was doing research and he focused almost exclusively on creating the algorithm. But he moved in to being the director of AI at Tesla. And now he spends 3/4 of his time on the data. Because now that he's building a car, it's not about having a better predictor, it's about getting all the data into a place where you can fit it into the algorithms.

And many engineers are in the exact same situation, spending enormous amounts of time inside the data. So making AI a real means that we need to make this process much more efficient. Next, let's move on to the next step in the workflow, which is getting the AI algorithm together. And this is the one that most people want to talk about.

It's of course, important to have direct access to many different algorithms used for classification and prediction, from regression into deep networks to clustering. And there's a variety of pre-built models developed by a broader community that you may want to start from and modify.

And while the algorithms and pre-built models are a good place to start, it's not enough. So often engineers are looking for examples to build off of. And so collecting and categorizing these examples is an important thing needed in terms of developing the AI model.

And the world is not sitting still. There's a broad AI community that's incredibly active. And so new models are coming out all the time. And the way that we support this is through the ONNX standard, which allows engineers to access models and different environments. And for us at MathWorks, we plug into that ONNX infrastructure and interchange standard, and then allow engineers to pull in models from other locations. And when training the engineers can use simulation to generate synthesized data.

And so let's take the case of a hydraulic pump used in oil extraction. You often know that critical failures are a case such as when the pump seal leaks. They rarely happen and they are very destructive, which makes it difficult to get the failure data. So you can build a model of the pump, run simulations to produce the signals that represent the failures.

And then these signals can be used to train the AI to detect future occurrences of these types of failures, real systems in the field. And we get those models into the field through our final stage, which is deployment.

And of course, deployment is the last step in the stage, but certainly not the least. Engineers need to be able to deploy AI. And at least for MathWorks, this is one place where we feel like we've spent our lives working on helping engineers get from their ideas to implementation through code generation.

And this allows the models to be deployed anywhere without having to rewrite the original models. You can take them to embedded systems through C code generation, to GPUs through CUDA generation and onto FPGAs through VHDL and Verilog.

So that's my pitch on the value of real world AI and how to get it into the field. Talk a little bit about flexible compute and data topology. This is a mouthful. And I came to this understanding from a debate with a friend of mine where I said the world is moving to the cloud.

And he said to me, no, world is not moving to the cloud. And I thought, well, that's just being silly. You can all see that cloud is where things are going. And he said to me, well, think about it, when you're an engineer, you're collecting data, probably storing that data, and you're computing and reporting on that data.

Sure, that's a pretty simple way of looking at the world. And I agreed with him. And he said, is all of that moving to the cloud, my answer was, of course it is. I can see it every day.

And his response was, is it always moving to the cloud. And it got me thinking, how is that move started and is all of it moving there. So at least for me, I grew up a child of the '70s in the US. And Mr. Peabody and his boy Sherman had this Wayback Machine. And if I set my date for 1988, I can go back to the way the topology was set up when I first became an engineer. There were sensors, there were storage systems that were huge.

In fact, I worked on one of these. We called it a washing machine because it was the size of a washing machine. And the disk packs were huge and stored very little information. The computers were in a room by themselves. and we all had terminals. And this was the state of the art.

If I come back, as I moved on in my career to the time about 1996, the separate topologies were still there and technologies, but they were much smaller. The sensors had shrunk. The storage units had shrunk to disks. And desktop workstations that come into vogue. Sparks and Apollos had replaced large computer rooms. And these things were expensive.

But by the end of the '90s, desktop computers have taken over. And the engineering workstation of the future was affordable by the average engineer. So that's the history that I was thinking about as I was arguing with my friend that everything was moving to the cloud.

So if we come back to today, his argument goes something like this-- we actually have multiple places where we can do computing and we can do data storage. And we really should figure out and be flexible. If we have hard real-time control needs, then we should move the data and the compute out to smart assets, smart sensors, smart actuators.

If we have real-time decisions that we need to make, then perhaps an edge system deployment is where the data and the compute power should be. But as you move into more business decisions and you have time-sensitive business needs, then perhaps moving compute and data to an OT system is the right choice. And lastly, regardless of where you're doing any of your decisions, you're eventually going to want to store all the data for historical purposes and to train your future AIs on what has come before.

His point to me was, you should be able to pick any and all of these. You shouldn't have to go in assuming from the beginning that we have one particular area where we will do our compute or we will store our data. And it was eye opening to me. And again it's humbling to think about all the different places that today engineers do their work. So, there is my case for flexible compute and the need to have a different topology.

So lastly, I'm going to talk a little bit about agile and what I mean by that. So I'm a child of the waterfall design. I get my requirements, I go to design, I go to implementation, I go to verification, I deploy, and I do maintenance.

And this is a very simple way of doing things. It's a very comforting way. And I think, as most of us know that have been practicing engineers, it rarely works this way, but certainly is a nice comforting feeling. And as I went on in my career, there was a notion of a spiral approach, which felt a little bit more connected to the real world where you loop through different phases on your way into deployment.

But more recently, we've seen DevOps and DevSecOps, where the idea is that you're in a continuous design, build, deploy, operate, monitor, maintain, feedback, plan, design, build, and repeat. So if you think a little bit about this, you collect your requirements at the beginning because there is a beginning. And then you move on to doing your model-based system engineering, which we talked about.

Because as I made the case earlier, systems are getting too complicated to just write down things and share them. The world has become global. Development teams move across different time zones and borders and organizations. And models are the best way to communicate that.

Models also allow you to do virtual integration and simulation so that you can test and collect additional data. Then there's code generation for deployment. That gets you your system out into the field.

There's a natural stage where you do verification and validation. But actually this comes earlier, again, with the virtual integration and models for simulation, but also the final stage to do your sign-off. And then up till now I've mostly followed a traditional either waterfall or spiral.

It's at the next point where things start to get a little bit interesting. One is that systems need to be configuration managed since changes will be made on the fly in the field. Also, systems like Jenkins to do continuous testing integration and allows engineers to no longer think about testing integration as a final stage but as something to do along the way and in operation.

Then when the system is released, you want to move into embedded systems and real-time operating systems, and/or, as I was making the case for flexible topologies, to the edge or to the cloud, taking advantage of Docker and Kubernetes and Databricks and other infrastructure storage frameworks.

And then you want to come back around and you might want to make adjustments and redesigns in your continuous process. Or you need to adjust what's going on in the field by doing predictive maintenance and being prepared to make changes before they become issues in the field.

The speaker before talked about the challenges in a modern aircraft. One of the things that I began to realize is that the cost advantage of making a fix in a planned way or in a predictive way versus an unscheduled aircraft grounding is a huge problem for the industry. And the industry has a tremendous amount of data that is trying to figure out how to extract that value from. And that's where AI and real-time AI deployments, either to the edge devices in the field or in the back-end OT systems have a real advantage to changing the way that we do business.

So there's my four pillars of digital transformation. And going to talk a little bit about how that's been deployed in the real world from the MathWorks working with different customers.

So I'll start with Edwards Air Force base. So they were working on the Predator. And they needed to accelerate the performance of essentially doing the flight quality and flight mechanics.

And the problem was that it took them 24 hours to process the data that came from one flight. So it wasn't in time for the next slide. So they moved from doing a desktop serial process to moving to the cloud in a parallel process. And they were able to complete their analysis in about 16 times faster than their original approach.

And the key for them was the ability to parallelize their code by moving from traditional desktop to the cloud in a fairly easy way. From their point, it took them days to move the code, not weeks, when they had originally tried to do it.

If we go to Boeing, their challenge was to develop a guidance navigation and control system for the X40 and to make it fly autonomously or with remote control. And they used model-based design to essentially streamline their software development and implementation.

So they moved their verification cycle down from months to days and deployment from months to days using code generation. And they were able to rapidly deploy new code changes and successfully test the flight quickly.

If we move to a system-to-systems, Lockheed Martin had a challenge when they completed the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Program. They also needed to help their customers determine how to develop a set of logistics sites and maintenance in a way that allowed them to be predictive, which is difficult on a new aircraft, to figure out how much to stock at different logistical sites.

So they built a simulation model using a discrete event simulation engine tied to the aircraft's component, performance, and data. Then using Monte Carlo simulations that injected additional random events into the models, they were able to come up with logistical algorithms to help the storage warehouses purchase the needed parts to keep the uptime of the aircraft at the required level.

We also talked about changing the world that we live in. And for a company like Rolls-Royce, they wanted to take an architectural approach and an agile approach to the way they developed aircraft engines. And this is very critical to them because they've got a long history of providing jet engines to power commercial aircraft. But they see a world where they'll need a mix of electric propulsion for aircraft and also small engines for personal mobility. And they want to be able to modularized the way that they develop their algorithms so that they can reuse as much as possible to get faster time to market.

Safran looked at engine health monitoring. Again, we mentioned that a couple of times today. The amount of data generated by the average engine throughout the world is in the amount of terabytes of data and picobytes of data. And that just has a tremendous ability to allow engineers and maintenance teams to get ahead of problems.

And Safran created a web-served model of the engines that their customers, the airlines, could come to to do predictive maintenance modeling and scheduling of downtime for the engines. Also, what's amazing to me is the fact that the tools can help us move beyond.

I forgot to mention at the beginning that I'm an aerospace engineer. And for me one of the things that was always inspiring was to think about spacecraft and moving beyond the world.

And so OHV used model-based design and model-based system engineering to design spacecraft that could dock and meet and move on. I'm cognizant of time. I think I'm pushing the bounds here of my time. So I'm going to just wrap up saying, also you can use AI to look at machine learning for not just customer data but also signals, such as radar and communication, and many more.

So hopefully I've helped you understand that digital transformation moves across the life cycle of today's engineering organizations. And that it will help us move into the future. So to keep on time, I'm going to stop here. So thank you.